Article by Tara Kosowski

Like many independent schools, Sacred Heart Academy Bryn Mawr (SHA) faced a variety of reactions from students following the 2016 presidential election. Some approached school leaders asking for a safe space to engage in difficult conversations outside the classroom. In recent years, SHA has taken significant steps to establish an inclusive dialogue practice, which has prepared the school community to moderate potential conflict generated by this year’s presidential election.

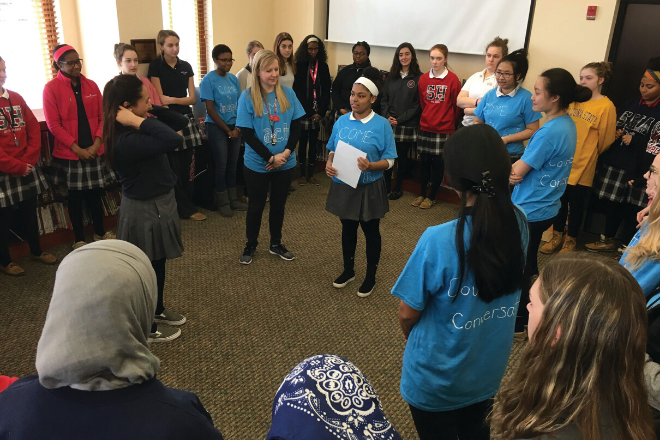

To instill the idea that all individuals show respect, acceptance and concern for themselves and for others, school leaders at the K-12 girls school outside Philadelphia have organized after-school meetings called “Courageous Conversations.” These gatherings give students an opportunity to discuss challenging topics and current events, and encourage active listening and productive civic participation.

From 3-8 p.m. on select Fridays, students gather to discuss topics such as gun control, race, immigration, American identity, and gender and sexuality. The first half of the night is spent “skill building,” in which facilitators establish a neutral space and ensure that everyone observes the agreed-upon expectations. In the second half of the night, students break into small groups to engage in dialogue around a topic determined by participating students.

Students are encouraged to independently lead each session, with faculty and staff moderators present to intervene or clarify, check understanding, or ask questions that take the learning deeper. But staff have yet to intervene, according to Kerri Schuster, co-director of the program and an upper school English teacher. By design, participating students are not passive consumers of information but leaders of critical exchange.

“In the classroom, the goal for students and teachers is more often than not to get to a final product or the right answer,” added Schuster. “And in our dialogue, we are very clear that there is no final product. The only reason you’re there is to learn more about why you think the way you do and why others think the way they do. So that setting frees students up a little bit to ask some more probing questions.”

Faculty and staff who observe sessions have received dialogue and facilitation training, and the program has been positively received. Dialogue training is now a part of every in-service day and plans for the next school year include implementing division-specific work and incorporating the programming into diversity committee meetings.

"We also accept that there will be times that we will make mistakes, but we will allow each other to learn from those mistakes. ‘Courageous Conversations’ gives us that common language and starting point."

Deirdre Cryor

Sacred Heart Academy Bryn Mawr

“Everyone benefits when you state clearly how to engage in dialogue,” said head of school Deirdre Cryor. “To be a community means that we accept that we will work together through the good, easy stuff as well as the difficult and challenging topics. We also accept that there will be times that we will make mistakes, but we will allow each other to learn from those mistakes. ‘Courageous Conversations’ gives us that common language and starting point.”

Launching the Dialogue

“Independent schools have a unique opportunity to engage in difficult conversations because everyone has chosen to be there,” said Kelly Weber, who established and co-directs the program with Schuster. “When you have that shared mission statement, it’s easy to turn back to that.”

For schools thinking of starting similar programs, Weber and Schuster recommend the following:

- Get buy-in. “One of the keys to our success was buy-in from the head of school,” explained Weber. SHA’s head “framed it in a way that said: This is who we are, this is what it means to be a Sacred Heart representative, and this is going to make our school better.”

- Develop clear ground rules or expectations of behavior that everyone should abide by. These enable participants to feel safe to engage and to develop trust in one another.

- Be non-judgmental. Participants will have the opportunity to explore other points of view and challenge one another’s beliefs in a positive way.

- Be inclusive. Participants need to feel valued and understand how their identities contribute to a diverse and rich community.

Tangible Results

One program outcome is that SHA has been better able to articulate its own identity and differentiate itself within its market. “There are a lot of assumptions about who we are. What we’re doing is digging down deep and defining [for ourselves] who are we,” Schuster explained. “We have used dialogue training to grow the school, find our strength and find how that drives diversity of thought and experience in our community.”

The “Courageous Conversations” program has also helped school leaders think about the dynamic between SHA and the Pennsylvania suburbs in which the school is located. “Working with students on dialogue training gives them the ability to navigate differences, toward greater understanding instead of [through] conflict and division,” said Cryor. “If our Sacred Heart graduates go into the world with these skills, I feel we have fulfilled our mission.”

School leaders have defined behaviors they do not want to see, such as political caricatures and harassment, and they plan to highlight positive political engagement opportunities including the school’s political science club and the student newspaper.

“At first, we were promoting dialogue training as an important tool to be used in the next election,” explained Schuster. “But as the program developed, I’ve instead started telling people: These are skills you are going to take with you for the rest of your life.”

Tara Kosowski is NBOA’s manager, editorial content, and assistant editor of Net Assets magazine.

Download a PDF of this article.