Article by Jamie Forbes, Learning Courage

When I came forward with my story in 2017, it was difficult to put into words my sexual abuse as a student at Milton Academy. I grew up in Milton, Massachusetts, where the boarding and day school is located, and had family connections on both sides that dated back more than 100 years. This connection was a source of both pride and expectation.

The summer before my freshman year, I joined my two cousins — both students at Milton — on an adventure bike trip through the countryside of northern Italy led by Rey Buono, a Milton Academy teacher. During that trip, I was sexually assaulted by Buono. While I confided in my cousins the events of that summer, we did not report the abuse to any adults. And as the school year commenced and Rey was assigned to me as my academic advisor, the abuse continued.

I felt a profound sense of shame, coupled with questions that I couldn’t seem to answer: Why do I keep ending up here when I hate it? Will I make it through Milton? What would my friends and family think if they found out? Why can’t I make it stop?

These were all questions that came up while I drifted off to sleep and followed me on my way to school. The shame congealed and settled into everyday life. I was so unhappy that I began to imagine the possibility of killing myself. Fortunately, one of my cousins, who travelled with me that summer, observing that I was depressed, reached out to his mom for help and relayed my story. His mom offered to send a letter to the administration at the school, telling them that Rey had sexually abused me.

To my surprise, life at Milton after this point was more or less quiet. Nobody at school asked me about the bike trip or whether anything had happened afterward. Why did nobody pull me aside to ask me questions about the abuse or how I was feeling? There was silence! The only thing I heard that related to me or consequences for Rey was that he would no long be my advisor or permitted to attend school bike trips.

Peers continued to be a major source of comfort to me through the rest of my years at Milton. They made me feel less like a fraud, and there was a certain safety in numbers. We had each others’ backs. With close friends and family, I opened up about what Rey had done to me. Through tenacity, fear, hard work, close friendships and some luck, I managed to stay at Milton until my graduation in 1985. On a beautiful day in June, my two grandfathers, both Milton graduates themselves, presented me with my diploma. I still felt like damaged goods, unworthy of their pride, but I made it.

A Foundation of Trust

Reflecting back on the incident that happened 40 years ago, it is easier for me to understand the complexities that come with addressing these incidents. I am not overlooking the lack of response — that was wrong. Rather, I recognize that the standard approach and knowledge of the long-term consequences for victims was very different than it is today. The fact is that the school failed me at the time. When what I really needed to hear was, “This wasn’t your fault,” and “We will take care of you,” I heard silence. And I internalized a clear and profound message: “We don’t care about you enough to ask what happened or how you’re doing.”

In the spring of 2016, the leadership at Milton sent a letter to alumni, parents and others in its community asking anyone who had experienced sexual abuse during their time at the school to share the details with them. With the support of my wife, two daughters and family, I returned to Milton nearly 40 years after first disclosing my abuse, hoping the response would be different.

And it was quite different. When I met with Todd Bland, the current head of school, the first thing he did was apologize for the school’s role in whatever I was about to share. This apology set a tone that allowed me to relax, shedding the first layer of my armor. Just hearing this apology gave me comfort that Todd wasn’t there to defend or deny the school’s role in my abuse. It opened me to the possibility that I could trust him. As with any relationship, that trust grew as he listened, demonstrated empathy, followed through on commitments, advocated for me and was available — not just in that initial conversation but throughout what became a nine-month long investigation into the school’s history of sexual abuse.

Another critical moment for me was the school’s response to the investigation’s findings. How transparent would the school be with what they learned? What would the tone and overall posture of the communication be about the results? Would they own the findings or try to minimize the school’s role? Would they respect me and others, who risked so much emotional energy and worried how the school would react in how they spoke about survivors?

Finally seeing the summary of the report findings was an important moment. And while it wasn’t all perfect, I understood the school’s position in the few areas where we disagreed because we had established a foundation of trust.

While telling my story has brought up many painful memories, it has also exposed an inner strength that I intuitively felt I had but had never accessed. In the years since, I have come forward publicly as one of the survivors in the report and founded Learning Courage, a nonprofit membership organization that helps schools protect their community from sexual abuse and misconduct, whether it happened in the past or present.

The main premise of our work is that the best outcomes from these incidents are when caring for those harmed is the primary goal. We call this taking a survivor-centered, trauma-informed and resiliency-based approach. Much like when physicians began apologizing to patients and saw malpractice claims plummet, when those who have been hurt feel cared for by their school, they are less likely to feel they need to fight the institution that was supposed to keep them safe. This article offers a sample of best practices recommended by Learning Courage, with details gleaned from survivors, school leaders and professionals who support schools on this topic.

Independent schools have an opportunity to provide a variety of supportive services for students, alumni, and employees in their communities. Establishing these services is one way for schools to show their commitment to community-wide well-being, care for victims and survivors, and developing policies and practices that are guided by integrity.

Best Practices in Misconduct and Abuse Response

When students and alumni come forward with their stories of surviving sexual misconduct and abuse, it is critical that the school’s leadership team respond with openness, empathy and a desire to help those harmed and protect those in their care today. That process takes place through investigating the reports with integrity and providing the necessary support for those involved.

Independent schools have an opportunity to provide a variety of supportive services for students, alumni, and employees in their communities. Establishing these services is one way for schools to show their commitment to community-wide well-being, care for victims and survivors, and developing policies and practices that are guided by integrity. Schools can exhibit these traits to show they are working towards and actually reducing sexual misconduct and abuse in their communities.

Supportive services can focus on many different areas that are important in healing from trauma, including emotional, therapeutic, financial, legal, living and learning accommodations. Schools should have transparent plans in place regarding supportive services that are readily available and easily accessible to the school community. This process is complex, but the supportive services you provide will help aid the process of a survivor sharing and healing from past or current incidents of sexual misconduct and abuse. Listening to and learning from these stories can also be an incredibly powerful way for your school to grow.

An example of this is the list below that compiles the list of services that should be available on your school’s website and handbooks.|

may differ depending on a school's available resources and policies.

Supportive Services for Current Students

Supportive services for current students should be included in the health and wellness section on your school’s website. These services should also be clearly identified in the student handbook and around campus (i.e., in the wellness center, common areas, dorms, classrooms, hallways, etc.) and include:

Clear Avenues for Student Assistance

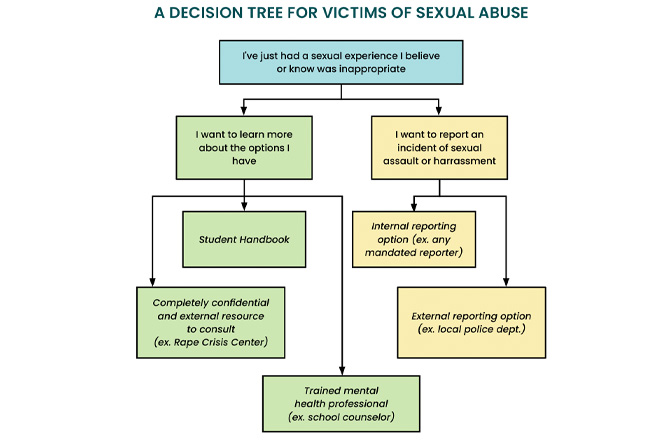

Clearly communicating your school’s sexual misconduct and abuse reporting policies creates transparency and opens up support channels for those seeking help. One way your school can do this is by creating and promoting a decision tree that explains where anybody can get support on campus (see image above).

Your decision tree should include multiple sources such as administrators involved with the misconduct committee or dedicated risk management team, school counselors, school nurses, the deans of students and more. It should also include cell phone numbers or other monitored phone numbers alongside names and titles. Those responsible for fielding calls must be appropriately trained in responding to reports of sexual misconduct and abuse.

Counseling and Medical Services

All medical professionals on campus should also be trained in caring for victims and survivors of sexual misconduct and abuse. Specifically, they should be trained in trauma response and be prepared with contacts and information about where students can receive medical care in the area.

Each school has different abilities to provide counseling services. Ideally, your school has licensed psychiatrists and/or counselors available to current students through your health and wellness centers on campus. These professionals should be on campus and available at all times when your school is in session. While not all schools have a dedicated resource at all times, your school can, at a minimum, have licensed counselors associated or contracted with your school who can be brought in to support your students. It is critical that these providers are trained on how to work with victims and survivors of sexual misconduct and abuse.

All medical professionals on campus should also be trained in caring for victims and survivors of sexual misconduct and abuse. Specifically, they should be trained in trauma response and be prepared with contacts and information about where students can receive medical care in the area.

Accommodations

Sexual misconduct and abuse will impact all aspects of a survivor's life, which is why it is important that your school have a response plan tailored to your ability to accommodate both reporting and responding parties.

As stated in our best practice philosophies, Learning Courage emphasizes the importance of policy adherence related to counseling, sanctuary policies, confidentiality and mandated reporting. Not only does your school need to be ready with these plans regarding different accommodations for reporting and responding parties, but you must also adhere to these plans when reports are disclosed. Furthermore, your institution should clearly state its accommodation abilities. Schools should create broad awareness for reporting options and be prepared to quickly enact these accommodations for the reporting and responding parties.

Accommodations for both reporting and responding parties of sexual misconduct and abuse include such items as:

- Academic accommodations.

- Switching class.

- Extra time on assignments.

- Flexible absence policies (being able to make up work they may have missed and not being punished for missing class due to circumstances).

- Residential accommodations (where applicable).

- Switching dorms.

- Moving into a single occupancy room.

- Moving off-campus to live with someone they feel is safe.

- Flexible leave policies.

- Allowing the reporting and responding parties own decisions on whether to stay enrolled or not throughout the investigation.

- Defined terms and policies.

Supportive Services for Alumni

Schools should also provide clear avenues for assistance for alumni who were victimized while attending the school, in addition to clearly established points of contact for alumni. These services should be readily accessible for alumni through your school’s website and include:

Counseling

Where possible, independent schools should provide alumni survivors with services similar to what current students receive. Consider, for instance, alumni access to counseling services, whether it be through a financial assistance fund or by providing clear information on how to access mental health counseling. Whatever your school decides, it should make resources for counseling easily available for alumni.

Arbitration/Legal Services

The goal for everyone should be to come to a resolution that involves minimal legal involvement. However, that is not always possible. Arbitration and restorative justice practices, when both parties agree to them, are highly preferred over legal proceedings. Arbitration and restorative justice are typically faster and much less expensive than involving lawyers. However, the potential for using these approaches is directly related to how you react and respond to those reporting harm. In some cases, the legal approach is unavoidable and dictated by the scenario.

Some schools provide arbitration and legal services to survivors of historic misconduct and abuse, but it is not a required component to supporting survivors. Oftentimes, this service could be counterproductive both to the survivor and to your school, as a survivor is not likely to trust an attorney assigned to them by your school. It may also be viewed as acting against your school’s interest to provide legal services to a survivor who may choose to take action against your institution.

Supportive Services for Employees

When a faculty member reports sexual harassment, misconduct or abuse, schools should be ready to provide the reporting party and those supporting that party with supportive services, such as through employee assistance programs.

Employees may find themselves involved with reports of harassment, misconduct or abuse through their duty to care for students and work with other adults. When a faculty member reports sexual harassment, misconduct or abuse, schools should be ready to provide the reporting party and those supporting that party with supportive services, such as through employee assistance programs (EAPs).

These programs should outline details such as whether your school refers legal counsel to employees, covers legal expenses for employees, and covers or refers employees to counseling services. This information should also be included in training for all employees so they know the services that your school makes available to them. Schools should also outline what protections they will be given for being, or being associated with, a reporting party (i.e., anti-retaliation policies, confidentiality, etc.). This prevents, for example, a teacher having to pay for legal services if a parent decides to file suit against the teacher who the family accuses of libelous behavior. Knowing they are protected from risk when supporting students after incidents demonstrates the school’s confidence in individuals and gives confidence to those responsible for delivering that care.

As school leaders, you care about your communities, which includes your students, employees, parents, alumni and board members. As such, it is important that your school outlines the ways you can and do support your community members when they have been impacted by sexual abuse or misconduct. Each school is unique in its own ability to provide supportive services to its employees. The most important thing is that your school has a plan that is well articulated for those services.